Report Release: Best Practices for Deploying EV Charging Stations

Vehicle electrification is overwhelmingly beneficial for society as a whole—even for nondrivers. The world doesn’t need any more cost-benefit analyses; they’ve already been done, and they show as much. And we should not doubt that people will buy electric vehicles (EVs). Sales are accelerating so rapidly that Bloomberg New Energy Finance warns the U.S. will hit an “infrastructure cap” in the mid-2030s due to a lack of charging stations. The questions we should be grappling with now are where to build EV chargers, who should own them, and how to make fast charging a sustainable business.

Rocky Mountain Institute’s new report, From Gas to Grid: Building Charging Infrastructure to Power Electric Vehicle Demand, addresses these questions in depth and offers some best practices for how different states might proceed with deploying charging infrastructure, given varying regulatory contexts and jurisdictions.

Deploying charging infrastructure so that it will support the burgeoning fleet of EVs while delivering benefits to all will require careful planning, robust testing and pilots, and appropriate incentives and guidance. And it will require the cooperation of an incredibly diverse group of stakeholders, including utilities, their regulators, state and municipal officials, automakers, charging station companies, community advocates, and more.

But that’s not all. Planners need to consider how many and what kinds of chargers will be needed and where they will be needed, both now and in a future in which personal vehicles are displaced by fleets of self-driving electric taxis offering more convenient mobility at a fraction of the cost of owning a vehicle.

Although it’s still hard to say exactly when the transition to “Mobility as a Service” will arrive, it is highly likely, if not inevitable, that it will arrive. RMI’s analysis shows that it could be well under way within a decade.

Viewed in this way, the oft-cited arguments against public investment in EVs and charging infrastructure take on a different character. If universal vehicle electrification is all but inevitable—and there is mounting evidence that it will deliver more than ample benefits to all of society, from Tesla drivers to those who don’t even own cars—we shouldn’t allow uncertainty about whether utilities should invest in extending the distribution grid to charging stations to slow down these much-needed infrastructure investments. And we shouldn’t worry about whether some people will benefit from access to charging stations a few years before everyone benefits from it. If that inclusive future is only a decade off, then why let these solvable short-term issues stand in the way of progress? Especially if that future features not just better mobility and cleaner air and less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, but also a greater share of renewables on the grid thanks to electricity demand that can be shifted in both time and space.

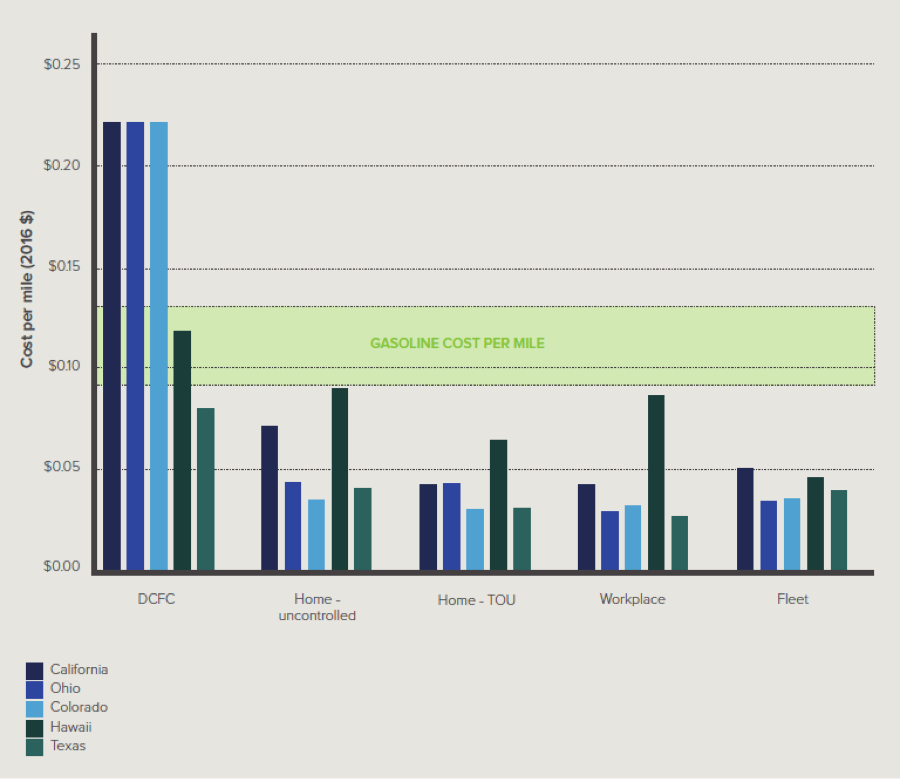

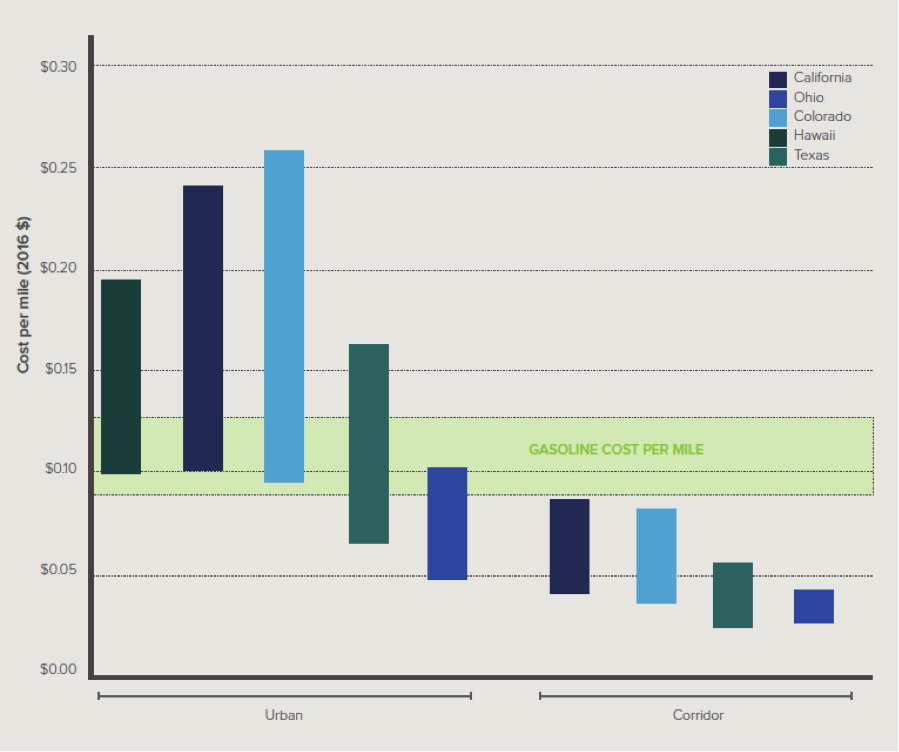

Instead, we should be thinking about the mix of slower Level 2 chargers that can charge up a vehicle in hours at a residence, workplace, or shopping area, and DC fast chargers (DCFC) that can top up a vehicle battery in minutes, and about which type of charger is best for a given application. In our report, we analyzed the cost of each type of charger in five different states and found that, while Level 2 charging is already competitive with gasoline refueling, high-speed charging on a DCFC is still too expensive in many cases.

If the electric vehicle revolution is to continue, we’ll have to find ways to make fast charging economical. For drivers, several key factors determine whether a fast charge can compete with gasoline refueling. The design of utility tariffs is one of these factors, and our report identifies some best practices in rate design that can help create a sustainable business case for DCFCs. Another key factor is how and where DCFC charging is done. Where chargers are likely to be frequently used, such as along commuting corridors, DCFC charging competes well with gasoline. But in urban locations where utilization rates are often lower and siting costs are higher, the economics of DCFC ownership are more challenging.

In order to keep the vehicle electrification revolution moving, each U.S. state needs to begin to grapple now with how to offer a favorable regulatory landscape, develop appropriate guidance and incentives for ownership of charging infrastructure, plan for chargers that will be well used and cost-effective, and ensure that all segments of society will have access to clean, electric transportation options. And the best way to do that is to start now—right now—by developing pilot projects to deploy chargers and gather data on what drivers need in each area, and then to start scaling them up. Our new report offers useful guidance, best practices, and lessons learned that all U.S. states can start using to get ready for a future of electric mobility.

Download From Gas to Grid: Building Charging Infrastructure to Power Electric Vehicle Demand.